Las cláusulas relativas agregan

información adicional a una oración al definir un sustantivo.

Por lo general,

se dividen en dos tipos: definición de cláusulas relativas y cláusulas

relativas no definitorias.

Definiendo cláusulas relativas

- The woman who lives next door works in a bank.

‘who

lives next door’ es una cláusula relativa definitoria. Nos

dice de qué mujer estamos hablando.

- Look out! There’s the dog that bit my brother.

- The film that we saw last week was awful.

- This is the skirt I bought in the sales.

¿Puedes identificar las cláusulas

relativas definitorias? Nos dicen qué perro, qué película y de qué falda

estamos hablando.

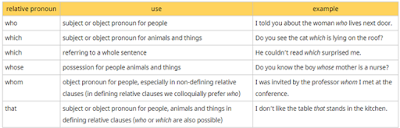

Pronombres relativos

Las oraciones de relativo son

generalmente introducidos por un pronombre relativo (por lo general quien , el

cual , de que , pero cuando , donde y que también son posibles)

Con oraciones de relativo podemos

utilizar quien o que hablen de personas. No hay diferencia en el significado

entre estos, aunque "quién" tiende a ser preferido en un uso más

formal.

Con oraciones de relativo podemos

utilizar quien o que hablen de personas. No hay diferencia en el significado

entre estos, aunque "quién" tiende a ser preferido en un uso más

formal.- She’s the woman who cuts my hair.

- She’s the woman that cuts my hair.

Podemos usar que o la que hablar

de las cosas. De nuevo, no hay diferencia en el significado entre estos, aunque

"que" tiende a preferirse en un uso más formal.

- This is the dog that bit my brother.

- This is the dog which bit my brother.